Quantification of Robotic Surgeries with Vision-Based Deep Learning

It is estimated that worldwide 300 million surgeries are performed annually. Around 15% of these surgical procedures are performed with the assistance of a robotic device. Such robotic surgeries have proven to be effective in reducing intra-operative complications (read: fewer errors during surgery), shortening the post-operative recovery time for patients (read: patients get better faster), and improving long-term patient outcomes.

The Surgical Triad

During a surgical procedure, robotic or otherwise, a surgeon must often navigate critical anatomical structures, such as nerves and blood vessels, avoid harming healthy tissue, and actively avoid potential complications, all the while tending to the main task at hand. This complexity is juxtaposed with the simplicity of the overarching goal of surgery: to improve post-operative surgical and patient outcomes. Recent studies have in fact shown that intra-operative surgical activity (what and how a surgical procedure is performed) can have a direct impact on long-term patient outcomes. Knowledge of this relationship can guide the provision of feedback to surgeons in order to modulate their future behaviour. We refer to the three components of intra-operative surgical activity, post-operative patient outcomes, and surgeon feedback as the surgical triad.

The Core Elements of Surgery

To better understand the relationship between intra-operative surgical activity and post-operative patient outcomes, we believe that the core elements of surgery must be first quantified in an objective, reliable, and scalable manner. This involves, for example, identifying what and how activity is performed during surgery.

The core elements of surgery can be understood by considering a particular robotic surgery (figure below), known as a robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP), in which the prostate gland is removed from a patient's body due to the presence of cancerous tissue. This procedure consists of multiple steps over time, such as dissection (read: cutting tissue) and suturing (read: joining tissue), which reflect the wha of surgery. Each of these steps can be executed through a sequence of manoeuvres, or gestures, and at a different skill level depicting low- or high-quality activity. Together, these elements reflect the how of surgery.

Quantifying the Core Elements of Surgery via Roboformer

In our most recent research, we design a deep learning framework, entitled Roboformer (a portmanteau of Robot and Transformer), that quantifies the core elements of surgery in an objective, reliable, and scalable manner. This framework is unified in that the same network architecture can be used, without any modifications, to achieve multiple machine learning tasks (i.e., quantify multiple elements of surgery). It is also vision-based in that is depends exclusively on videos recorded during surgery, which are straightforward to acquire from surgical robotic devices, to perform these machine learning tasks.

Phase Recognition

Can we reliably distinguish between surgical steps?

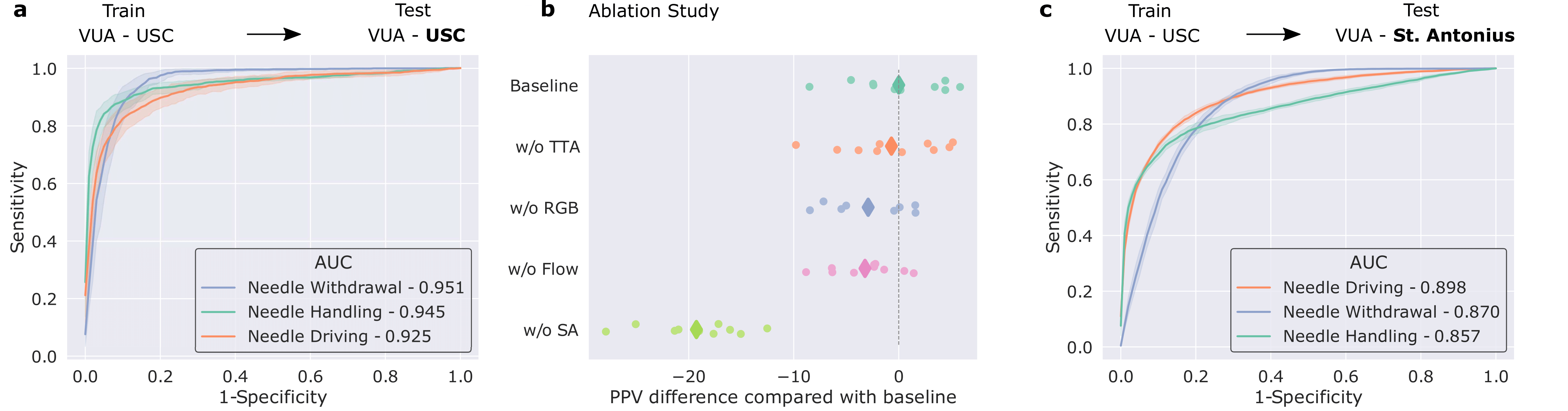

We trained our framework to distinguish between three distinct surgical sub-phases (read: steps): needle handling, needle driving, and needle withdrawal. These reflect periods of time during which a surgeon first handles a needle to drive it through some tissue before withdrawing it as part of the suturing process. Specifically, our framework was trained on data from the University of Southern California (USC) and deployed on unseen videos from USC and on unseen videos from a completely different medical centre (St. Antonius Hospital located in Gronau, Germany).

We show that our framework generalizes (read: performs well) to unseen surgical videos and those from unseen surgeons across distinct medical centres. While the former is evident by the strong performance (AUC > 0.90) achieved when the framework was deployed on USC data, the latter is supported by the strong performance (AUC > 0.85) when it was deployed on data from St. Antonius Hospital. We defer an explanation of the ablation study and results to the manuscript.

Gesture Classification

Can we reliably distinguish between surgical gestures?

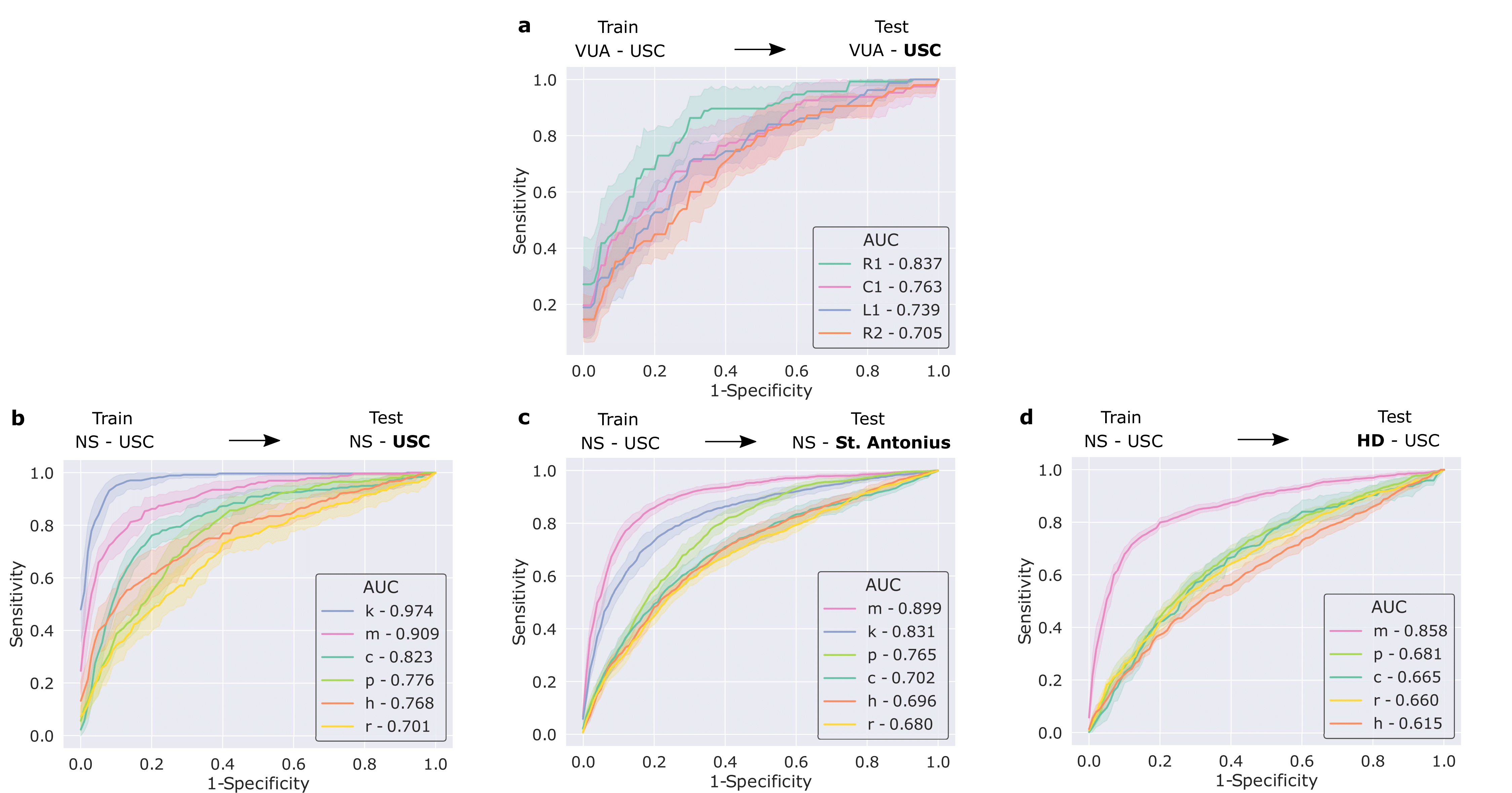

We also trained our framework to distinguish between surgical gestures (read: manoeuvres) commonly performed by surgeons. These reflect the decisions made by a surgeon over time about how to execute a particular surgical step. Once again, our framework was trained on data from USC and deployed on unseen videos of the same surgery (RARP) from USC and St. Antonius Hospital. In this setting, we also deployed our framework on videos from an entirely different surgical procedure, known as a robot-assisted partial nephrectomy (RAPN), in which a portion of a patient's kidney is removed due to the presence of cancerous tissue.

We show that our framework generalizes to unseen videos, surgeons, medical centres, and surgical procedures. This is evident by its strong performance (see below) across the board in all of these settings.

Skills Assessment

Can we reliably distinguish between low- and high-skill activity?

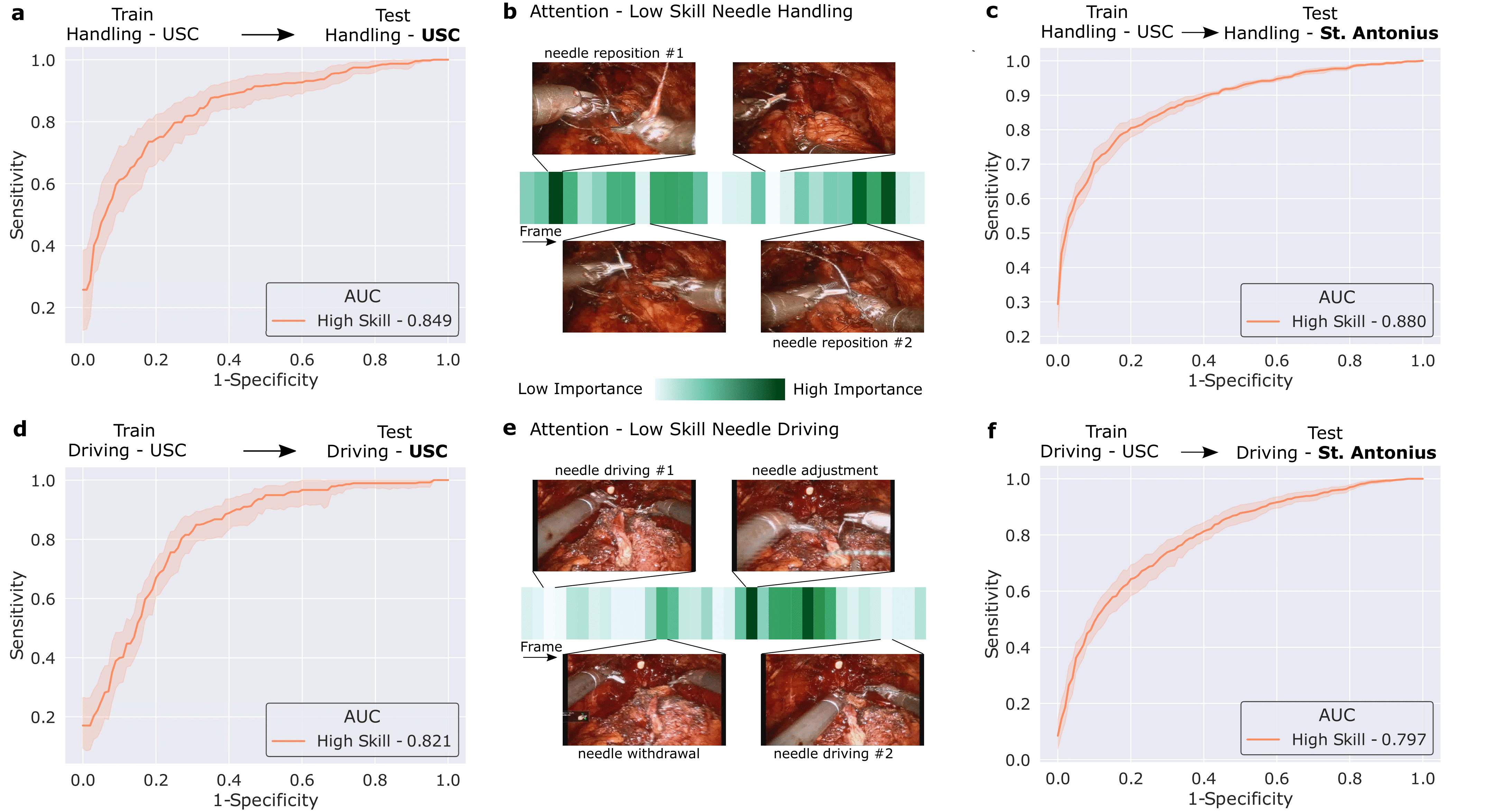

We then trained our framework to delineate surgical activity depicting low and high technical skill. This activity ranged from how the surgeon handled a needle during the suturing step (needle handling) and how the surgeon drove the needle through the tissue (needle driving). For needle handling, a low-skill assessment was based on the number of times a surgeon had to reposition their grasp of the needle (more repositions = lower quality). For needle driving, a low-skill assessment was based on the smoothness with which it was performed (less smooth = lower quality). As before, we trained our framework on data from USC and deployed it on data from both USC and St. Antonius Hospital.

We show that our framework, once again, generalizes to unseen videos, surgeons, and medical centres. This is evident by its strong performance (AUC > 0.80) across the skills assessment tasks and clinical settings. Our framework (which is based on a Transformer architecture) also naturally lends itself to explainable findings. Below, we illustrate the relative importance of individual frames in a surgical video, as identified by the framework, and show that the frames with the highest level of importance do indeed align with the ground-truth low-skill assessment of the video segments.

Combining Elements of Surgery

How do we practically leverage the findings of this study?

Thus far, we have presented our machine learning tasks, which quantify the various elements of surgery, as independent of one another. Considering these tasks in unison, however, suggests that our framework can provide a surgeon with reliable, objective, and scalable feedback of the following form:

When completing stitch number 3 of the suturing step, your needle handling (what - sub-phase) was executed poorly (how - skill). This is likely due to your activity in the first and final quarters of the needle handling sub-phase (why - attention).

Such granular and temporally-localized feedback allows a surgeon to better focus on the element of surgery that requires improvement. As such, a surgeon can now better identify, and learn to avoid, problematic intra-operative surgical behaviour in the future.

Translational Impact

How do our findings translate to impact?

Our findings provide the initial evidence in support of the eventual use of deep learning frameworks in the domain of surgery. To begin, the ability of our framework to generalize to videos across a wide range of settings (e.g., medical centres and surgical procedures) should instill surgeons with confidence as it pertains to its clinical deployment. Furthermore, our framework's ability to provide explainable results, by pinpointing temporal frames which it deems relevant to its prediction, has a threefold benefit. First, explainability can improve the trustworthiness of an AI framework, a critical pre-requisite for clinical adoption. Second, it allows for the provision of more targeted feedback to surgeons about their performance. This, in turn, would allow them to modulate such performance as a means to improve patient outcomes. Third, an element of explainability implies improved framework transparency and is viewed, by some, as contributing to the ethical deployment of AI models in a clinical setting.

Moving Forward

Where do we go from here?

We see several worthwhile avenues to explore in the near future. One such avenue is the study of the degree of algorithmic bias exhibited by our proposed deep learning framework against surgeon cohorts. This is critical in this context of surgical feedback as a biased system can disadvantage certain surgeons (e.g., those from different age groups) and thus affect their ability to develop professionally. These considerations would ensure that the entire pipeline of surgeons from surgical residents to fellows and attendings are safely equipped to identify positive and negative behaviours in surgical procedures, can incorporate these discoveries into future surgeries, and ultimately improve patient outcomes. We hope the broader community joins us in this endeavour.

Acknowledgements

We would also like to thank Wadih El Safi for lending us his voice.