A clinical deep learning framework for continually learning from cardiac signals across diseases, time, modalities, and institutions

Clinical data, that which are collected within hospitals or even through wearable sensors, can exhibit differences across space and time. For example, cardiac signal data collected from patients living in La Paz, Bolivia (3.7km above sea level) might differ from that collected from patients living by the Dead Sea, Jordan (413m below sea level). Moreover, such data can differ over time due to factors related to seasonality. Irrespective of the cause of the change, the end result is the same; a shift in the distribution of the clinical data that are collected.

Such distribution shift poses a challenge to existing deep learning systems that are accustomed to learning with data that are independent and identically distributed. In these settings, deep learning systems are likely to generate incorrect predictions, negatively affecting patient care, and compromising their trustworthiness amongst stakeholders within healthcare. To overcome this challenge, we propose a continual learning framework that allows for the design of clinical deep learning systems that remain robust to common distribution shifts. To better understand this framework, we discuss continual learning more broadly next.

What is Continual Learning?

At a high-level, continual learning involves a single network that achieves tasks that are streamed in a sequential manner. This setting can be visualized below where the network first achieves task A when exposed to data from distribution A (e.g., this can be data from the winter months). It then transitions to solving task B when exposed to data from distribution B (e.g., this can be data from the summer months). At the same time, the network must continue to perform well on data it has been exposed to in the past (namely, data from distribution A). Unfortunately, deep learning systems which are exposed to such an environment are prone to forgetting how to achieve tasks previously seen in the past, a phenomenon known as catastrophic forgetting. This is acutely problematic for clinical deep learning systems given the prevalence of environments within healthcare that exhibit distribution shift.

Continual Learning of Physiological Signals (CLOPS)

In our Nature Communications paper, we proposed a continual learning framework, entitled CLOPS, that exploits what is known as a replay buffer. A replay buffer can be thought of as a 'bag' in which we store data points and from which we can retrieve data points during the learning process (see visualization below). Here, we train a network on data from distribution A, as before However, once that task has been achieved, we identify the most informative datapoints in that distribution and store them in a buffer. To determine which data points are most informative, we learn a parameter associated with each data point in the task that acts as a proxy for the difficulty with which that data point is classified by the network. Upon training the network on data from distribution B, we acquire the most informative datapoints from the buffer and replay them alongside the data from the current task. To determine which data points to acquire, we exploit uncertainty-based acquisition functions (from the active learning literature) which identifies data points that the network is most confused about.

The intuition is that by replaying instances from the past, we can nudge the network into a parameter space that is favourable for solving tasks both in the past and the present.

Cardiac Arrhythmia Diagnosis

To evaluate our framework, we task a network with identifying abnormalities in the functioning of the heart (also known as cardiac arrhythmia diagnosis) while in the presence of different types of distribution shift. In short, cardiac arrhythmia diagnosis can be achieved as shown below. It involves mapping an electrocardiogram (ECG) signal to a probability distribution over distinct cardiac arrhythmia classes, where each probability indicates the likelihood that the signal belongs to a particular class. A classification can then be made by identifying the class with the highest probability assigned to it.

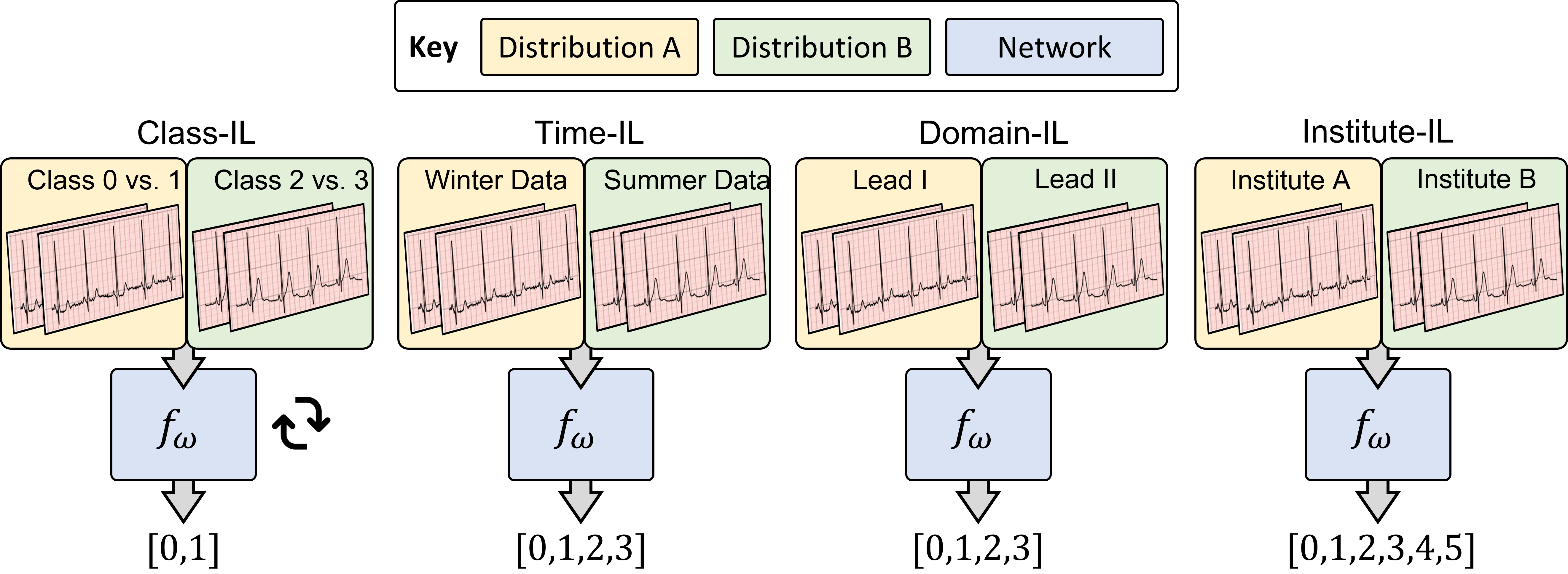

Mimicking Realistic Distribution Shifts

We explore four distinct types of distribution shifts (see visualization below). Class incremental learning (Class-IL) evaluates the ability of a network to adapt to environments characterized by unseen cardiac arrhythmia classes (read: distinct diseases). Time incremental learning (Time-IL) evaluates the ability of a network to adapt to data collected at different timepoints during the year. Domain incremental learning (Domain-IL) evaluates the ability of a network to adapt to data from different modalities. lastly, institute incremental learning (Institute-IL) evaluate the ability of a network to adapt to data from distinct medical centres. Overall, we have chosen these scenarios to cover a wide range of distribution shifts that are likely to occur within a clinical setting.

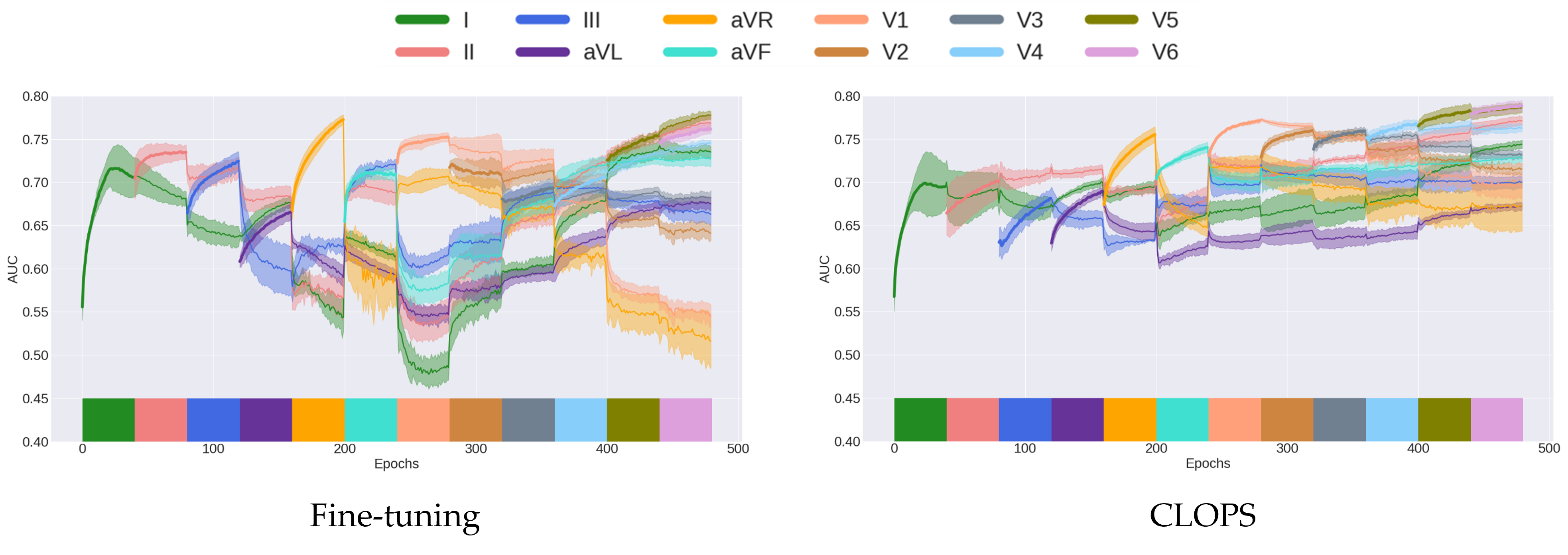

Mitigating Catastrophic Forgetting

We begin by visualizing the phenomenon of catastrophic forgetting. In the visualization below (left), we show the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) on data points in the validation set that is achieved by a fine-tuning network that is sequentially exposed to 12 distinct tasks (from different domains). The coloured blocks indicate the epochs (read: time) during which the network is learning to solve that particular task. We can see that the network learns to solve tasks while training on them, however quickly forgets how to achieve them upon transitioning to subsequent tasks. This is evident by the dramatic drop in the AUC as the network transitions to subsequent tasks. Such behaviour, which is catastrophic forgetting in action, is mitigated when deploying the CLOPS framework (see visualization below on the right). Namely, the dramatic drops in the AUC are significantly mitigated.

Comparison to State-of-the-Art Methods

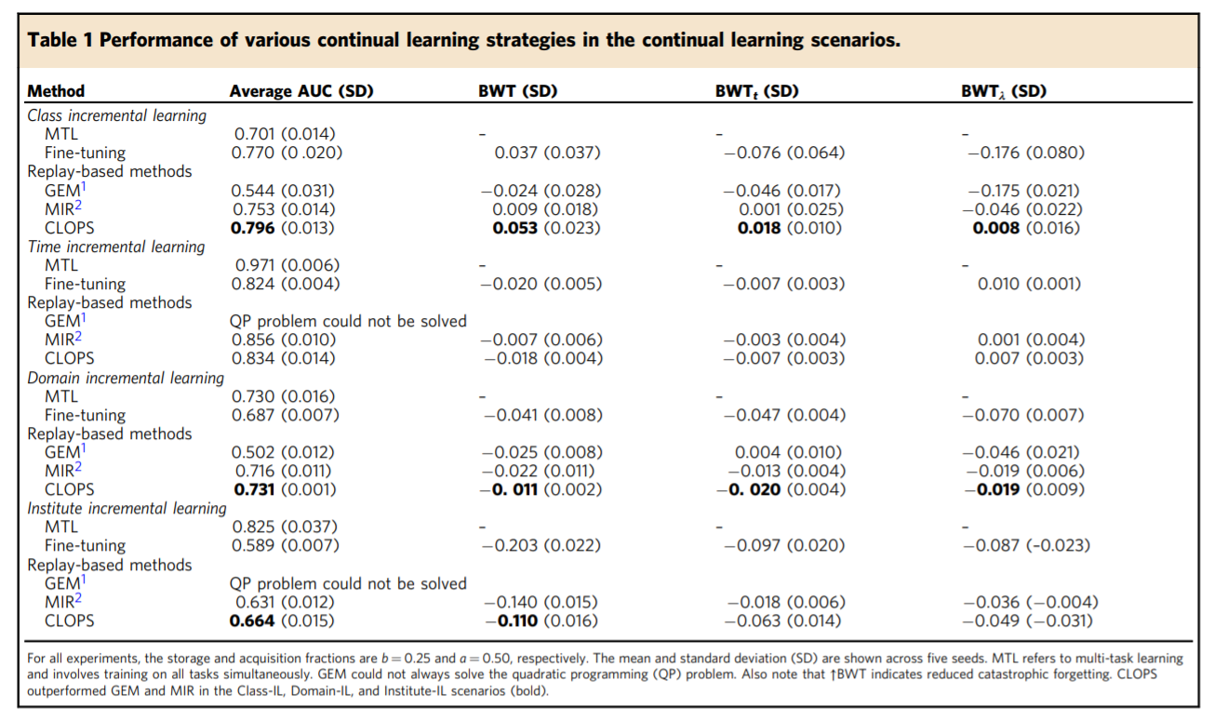

More broadly, we compare the performance of CLOPS to that of state-of-the-art baseline methods (such as GEM and MIR) across all four types of distribution shifts. The results are presented in the table below, where BWT reflects backward transfer and is an evaluation metric that reflects the degree of catastrophic forgetting (higher is better). We find that CLOPS outperforms the baseline methods in three of the four continual learning scenarios (Class, Domain, and Institute-IL). Such a finding suggests that CLOPS can be of value as a framework that instills deep learning systems with dynamic robustness, a critical feature of trustworthy systems that are to be deployed within clinical settings.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Abdel Halim Hafez and Farid Al-Atrash for lending us their voice.