Human visual explanations mitigate bias in AI-based assessment of surgeon skills

Artificial intelligence can assess quality of surgeon skills

The activity of a surgeon during surgery can directly impact patient outcomes. To assess the quality of this activity reliably and at scale, recent studies have leveraged emerging technologies suchh as artificial intelligence (AI). For example, in a study recently published in Nature Biomedical Engineering, we presented an AI system that can assess the skill-level of surgical activity based on a video of such activity. This system, which we refer to as SAIS, can be used by medical boards to credential surgeons and by hospitals to grant surgeons the privilege to operate on patients.

Bias of AI-based skill assessments is underexplored

With AI-based skill assessments likely to inform high-stakes decisions (read: surgeon credentialing and operating privileges), it is critical that these assessments do not disadvantage one subcohort of surgeons over another (e.g., novices vs. experts). For example, if AI-based skill assessments are consistently less reliable for one subcohort than for another, then this could unfairly deny surgeons the privilege to operate on patients (even if they are qualified to do so). We refer to this discrepancy in the reliability of the skill assessments across subcohorts as a bias. Despite its ramifications on the field of surgery, the potential bias of AI-based skill assessments remains underexplored.

Measuring and mitigating the bias of AI-based skill assessments

In our most recent research, published in npj Digital Medicine, we first inspect the bias of skill assessments produced by SAIS. Namely, we look for a discrepancy in the reliability of the skill assessments across distinct surgeon subcohorts (e.g., novices vs. experts). To mitigate this bias, we leverage a strategy of teaching an AI system to focus exclusively on relevant video frames when performing the skill assessment. Addressing these open questions improves the transparency of SAIS and contributes to its ethical deployment for the purpose of surgeon credentialing.

Measuring the bias of SAIS' skill assessments

Are AI-based skill assessments equally reliable for all surgeons?

We trained SAIS to assess the skill-level (low vs. high skill) of two distinct surgical activities: needle handling and needle driving. These activities are often performed in succession by a surgeon while suturing (read: joining tissue). Specifically, to probe SAIS' ability to generalize (read: perform well) to real-world data from different settings, we trained it on data exclusively from the University of Southern California (USC) and deployed it on previously-unseen videos from USC and from completely different hospitals: St. Antonius Hospital, Germany (SAH) and Houston Methodist Hospital, USA (HMH).

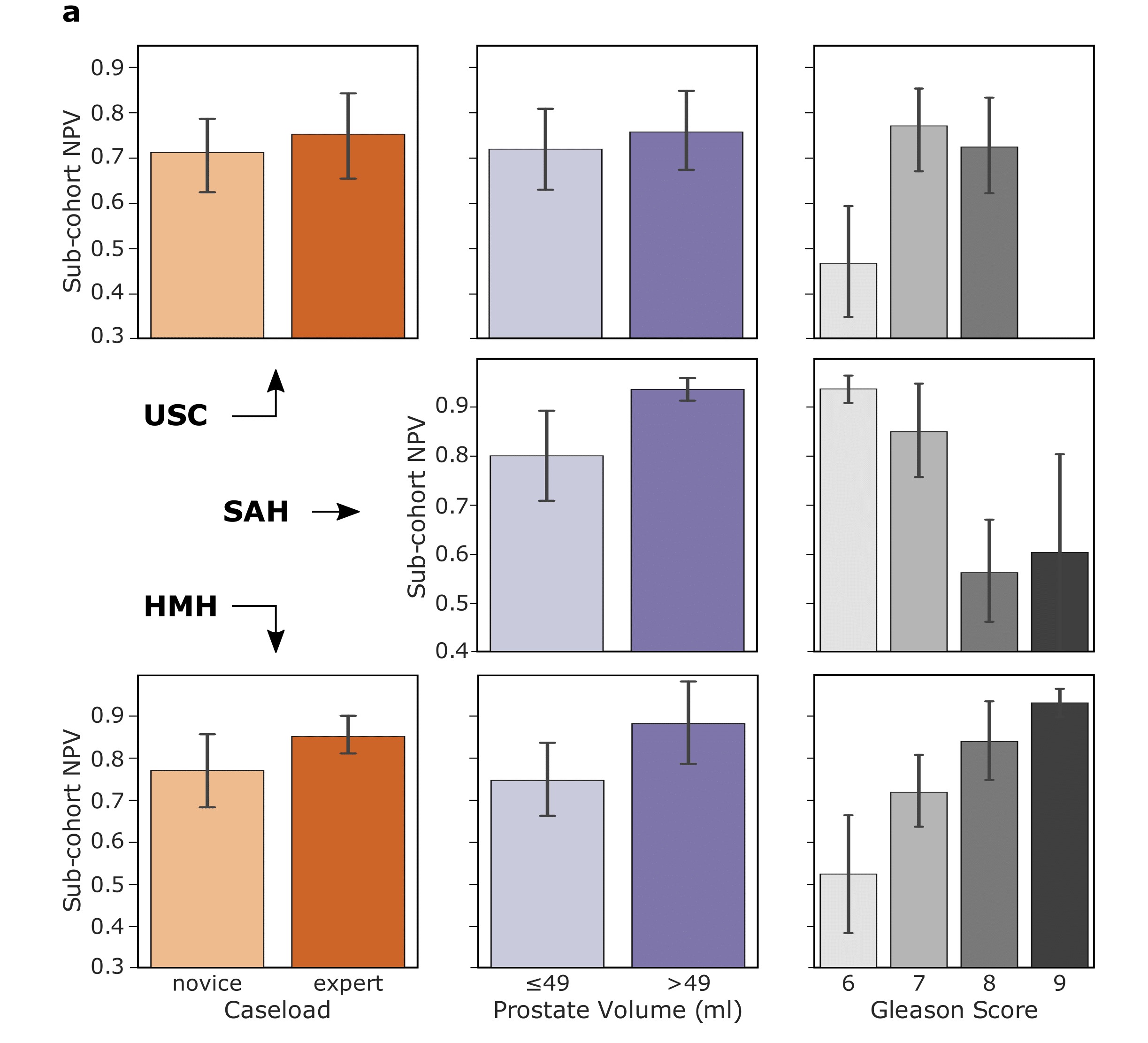

To assess the reliability of skill assessments, we look at their negative predictive value (NPV): the proportion of AI-based low-skill assessments which are in fact low-skill. A discrepancy in the negative predictive value across subcohorts implies that surgeon performance is erroneously down-rated by the AI system, and would therefore be unfairly prevented from operating on patients.

We show that SAIS, in some cases, does indeed exhibit an underskilling bias. This is evident by, for example, the discrepancy in the negative predictive value for novices (0.70) and experts (0.75) operating at USC. In our publication, we also show that SAIS exhibits an overskilling bias, where it erroneously upgrades surgeon performance.

Mitigating the bias of SAIS' skill assessments

How can we mitigate the underskilling and overskilling bias?

One potential source of the bias is that SAIS is learning to perform skill assessments by latching onto unreliable signals in the surgical videos. While these unreliable signals, or "shortcut" features, might correlate with skill-level in the data presented to SAIS, they are not reflective of the true skill-level more generally. To address this issue, and after having experimented with various strategies, we decided to teach SAIS to focus exclusively on relevant video frames when performing skill assessment. Specifically, we tasked SAIS with identifying important video frames (annotated by expert surgeons) alongside performing skill assessment. We hypothesized that doing so would prevent it from latching onto shortcut features. The details of this approach, which we refer to as TWIX, can be found in a concurrent publication in Communications Medicine.

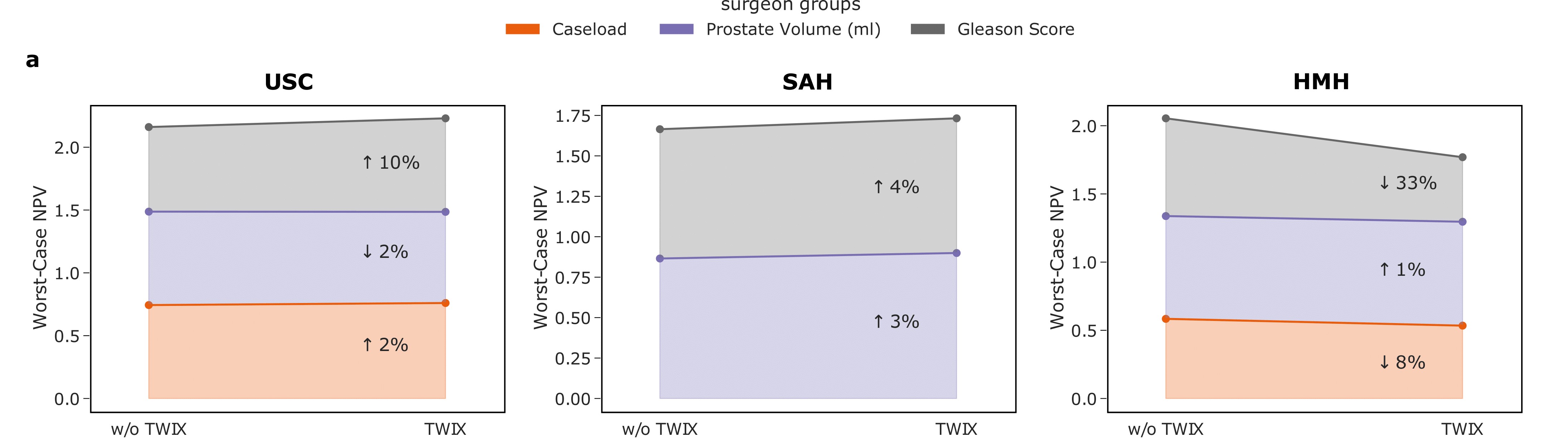

We show that TWIX, in some cases, drastically mitigates the underskilling bias. This is evident by the improvement in the worst-case negative predictive value (read: the reliability of skill assessments improves for the previously-disadvantaged subcohort). For example, at USC, the worst-case NPV improves by up to 10%. We also demonstrate that TWIX simultaneously mitigates the overskillig bias (results not shown).

Improving the reliability of AI-based skill assessments

Does TWIX confer any additional benefits?

We hypothesized that TWIX, by potentially alleviating the dependence of an AI system on shortcut features, can also improve the overall skill assessment performance of SAIS. We therefore deployed SAIS, after having been trained with TWIX, on data from USC, SAH, and HMH.

We show that TWIX does indeed improve the reliability of the skill assessments (read: better aligned with ground-truth skill assessments). This is evident by the improvement in the AUC of the AI-based skill assessments. For example, at USC, the AUC increases from 0.849 to 0.866. Similar improvements can be seen at the remaining hospitals.

Outlining the translational impact

What are the implications of our study?

Our study emphasizes the importance of considering the ecosystem in which an AI system is likely to be deployed. Although the absolute performance of an AI system is informative, a discrepancy in this performance across subcohorts can result in the unfair treatment of stakeholders. Such a discrepancy would have gone undetected were it not for an in-depth bias analysis. It is equally critical to design strategies that can simultaneously mitigate different types of algorithmic bias (underskilling and overskilling bias) for multiple sytems (needle handling and needle driving skill assessment systems). This ensures we develop trustworthy AI systems that best serve surgeons and patients alike.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Abdel Halim Hafez for lending us his voice.