A multi-institutional study using artificial intelligence to provide reliable and fair feedback to surgeons

Surgeons seldom receive feedback on their performance

Surgeons operate in a high-stakes environment where the ultimate goal is to improve patient outcomes (e.g., treat cancer). Professionals who operate in high-pressure settings, such as elite athletes, tend to receive feedback as a means of improving their performance for the future. However, surgeons seldom receive feedback about their performance during surgery. This is because the provision of feedback can be time-consuming, often requiring a peer surgeon to review an entire surgical procedure, subjective, where the feedback is dependent on the preferences of the reviewing surgeon, and inconsistent, varying from day to day and across surgeons. Such characteristics imply that feedback, if provided, is unlikely to be useful for the receiving surgeon. This hinders the ability of surgeons to learn from their past mistakes and master technical skills necessary for surgery. As such, patient outcomes are likely to be compromised.

Artificial intelligence can provide surgeon feedback

One way to provide surgeons with feedback about their performance is through artificial intelligence (AI). For example, an AI system can review a video of a surgical procedure performed by a surgeon and assess the skill-level of that surgeon's activity. These skill assessments can help reinforce optimal surgical behaviour and nudge surgeons to improve upon subpar performance.

In a study published in Nature Biomedical Engineering, we presented an AI system which can assess the skill-level of a surgeon's activity during a robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP), a procedure in which a cancerous prostate gland is removed from a patient's body. Importantly, our AI system, which we refer to as SAIS, can also provide a visual explanation for its skill assessment, informing you of why that skill assessment was made. Specifically, the explanation consists of highlighting video frames deemed relevant for the skill assessment.

Quality of AI-based explanations remains elusive

Although SAIS, and other AI systems, can complement their decision-making with explanations, it remains an open question whether such explanations are reliable. Namely, are AI-based explanations consistent with explanations that would have been provided by surgeons had they reviewed the exact same surgical video? Addressing this question with the affirmative would imply that AI-based explanations can be used as a teaching aid to surgeons, directing them to specific behaviour that can be improved upon.

Evaluating the reliability and fairness of AI-based explanations

In our most recent research, published in Communications Medicine, we evaluate the reliability of AI-based explanations by comparing them to ground-truth explanations provided by expert surgeons (see figure). Recognizing the importance of delivering feedback that is fair to all surgeons, we also investigate whether AI-based explanations are consistently reliable for all surgeon subcohorts (e.g., novices vs. experts). A discrepancy in the quality of feedback across subcohorts could unfairly hinder the professional development of one of the subcohorts. To improve the reliability and fairness of these explanations, we teach the AI system to mimic the ground-truth explanations that otherwise would have been provided by expert surgeons.

Evaluating the reliability of AI-based explanations

Do AI-based explanations align with human explanations?

We trained SAIS to assess the skill-level (low vs. high skill) of two distinct surgical activities: needle handling and needle driving. These activities are often performed in succession by a surgeon while suturing (read: joining tissue). Specifically, to probe SAIS' ability to generalize (read: perform well) to real-world data from different settings, we trained it on data exclusively from the University of Southern California (USC) and deployed it on previously-unseen videos from USC and from completely different hospitals: St. Antonius Hospital, Germany (SAH) and Houston Methodist Hospital, USA (HMH). By focusing exclusively on low-skill videos, we then compare SAIS' explanations (which we refer to as attention) to those provided by expert surgeons, quantifying their overlap with the area under the precision recall curve (AUPRC) (higher is better).

We show that SAIS' explanations often align, albeit imperfectly, with those provided by expert surgeons. This is evident by the mediocre overlap (AUPRC < 0.63) between the explanations when SAIS was deployed on data from USC, SAH, and HMH to assess the skill level of needle handling.

Measuring the fairness of AI-based explanations

Is there a discrepancy in the quality of AI-based explanations across surgeon subcohorts?

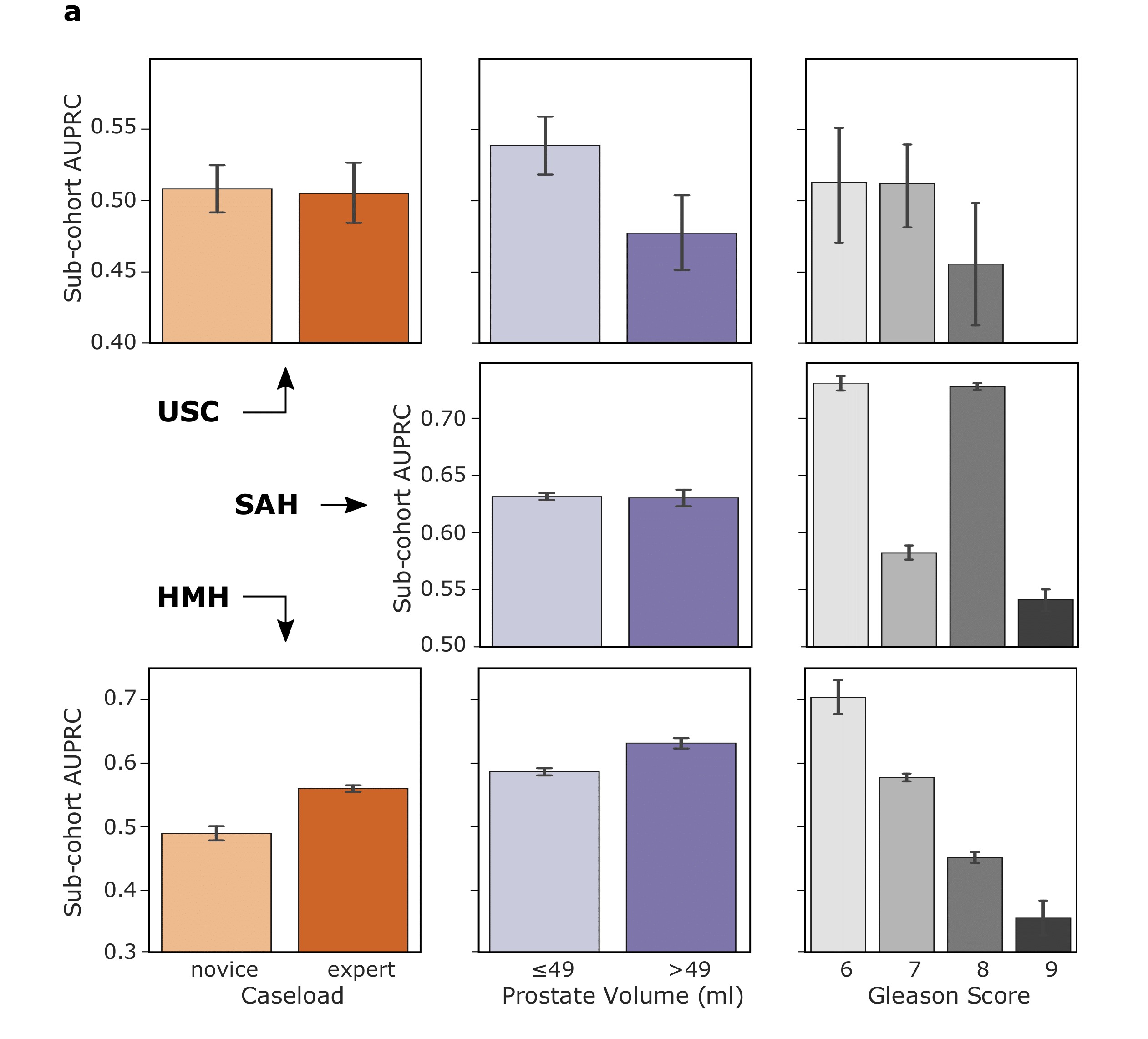

We also inspected the reliability of the AI-based explanations when generated for different surgeon subcohorts. For example, does SAIS generate explanations of higher quality (higher AUPRC) for expert surgeons than for novice surgeons? We therefore quantified the discrepancy in the AUPRC of the AI-based explanations for surgeons with different caseloads (read: total number of surgeries performed in their lifetime), and those who operate on prostate volumes of different sizes and varying cancer severity levels (Gleason Score).

We show that SAIS exhibits an explanation bias against surgeon subcohorts. This is evident, for example, by the discrepancy in the AUPRC for surgeons operating on prostate volumes of different sizes. For example, at USC, the AUPRC is 0.54 and 0.48 for surgeons operating on small and large prostate glands, respectively.

Improving the reliability of AI-based explanations

How can we improve the quality of explanations generated by an AI system?

We then explicitly taught SAIS to mimic the ground-truth explanations provided by human experts. In other words, we provided a supervisory signal in the form of human visual explanations from which SAIS can learn to identify important video frames. We refer to this approach as TWIX (training with explanations).

We show that TWIX does indeed improve the reliability of AI-based explanations. This is evident by the higher AUPRC (read: increased alignment between AI-based and human explanations) achieved by TWIX compared to the standard explanation approach (attention). For example, at USC, TWIX and attention achieved AUPRC of 0.488 and 0.677, respectively.

Improving the fairness of AI-based explanations

Does TWIX also help mitigate the explanation bias?

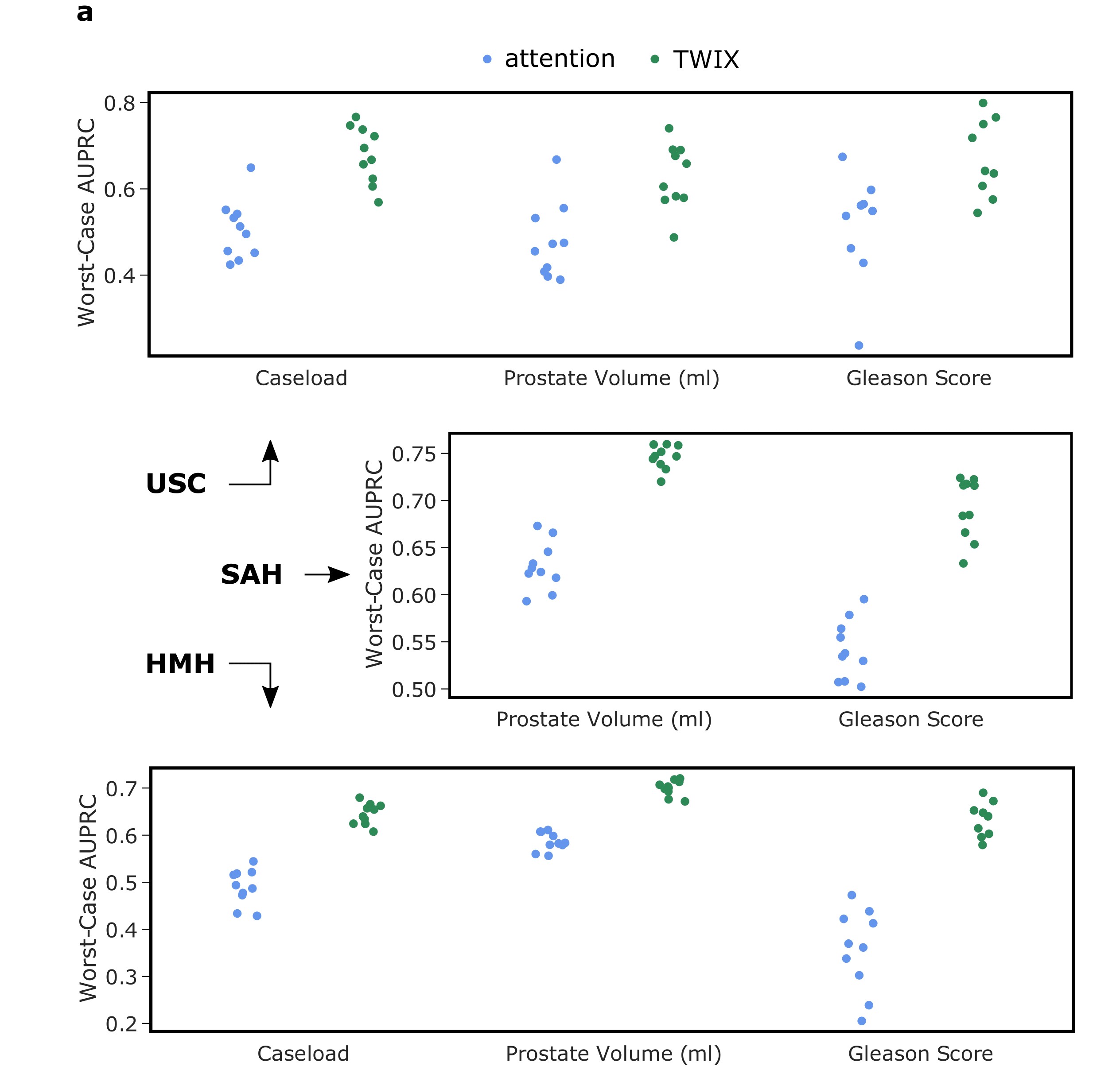

Inspired by the promising finding that TWIX improves the reliability of AI-based explanations, we also investigated whether TWIX can help mitigate the explanation bias (read: discrepancy in quality of explanations across surgeon subcohorts). We measured this by observing whether the previously-disadvantaged surgeon subcohort now receives higher quality feedback (after introducing TWIX). Therefore, an improvement in this worst-case AUPRC would indicate a reduction in the explanation bias.

We show that TWIX, in some cases, can drastically mitigate the explanation bias exhibited by SAIS. This is evident by the improvement in the worst-case AUPRC after introducing TWIX into the AI system's learning process. For example, at USC, and for surgeons with different caseloads, the worst-case AUPRC improved from 0.50 to 0.70.

Outlining the translational impact

What are the implications of our study?

Our study emphasizes the importance of investigating the reliability and fairness of AI-based explanations by comparing them to explanations provided by human experts. Without such an analysis, the deployment of SAIS could have provided surgeons with inaccurate feedback and unfairly treated surgeon subcohorts. By proposing TWIX, which improves both the reliability and explanations of AI-based explanations, we can contribute to the development of AI systems that are trustworthy and ethical. These characteristics are critical to the ultimate adoption of SAIS as a tool for the provision of surgeon feedback in an objective, consistent, and scalable manner.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Melhem Barakat for lending us his voice.